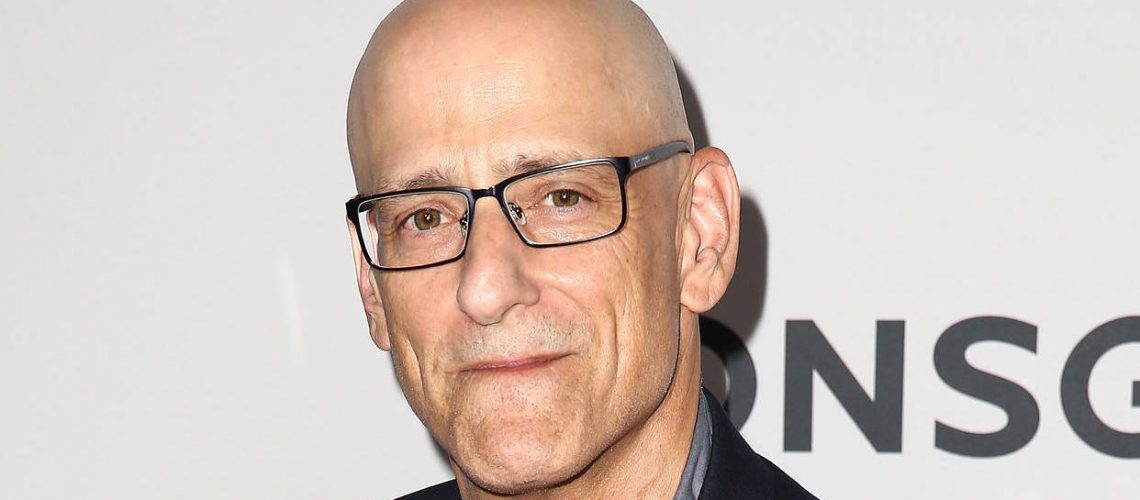

Edgar Award-winning & Internationally Bestselling Author Andrew Klavan

Award-winning author, screenwriter and media commentator Andrew Klavan is the author of such internationally bestselling novels as True Crime, filmed by Clint Eastwood, and Don’t Say A Word, filmed and starring Michael Douglas. Klavan has been nominated for the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Award five times and has won twice. His books have been translated around the world. He was dubbed by Stephen King: “The most original American novelist of crime and suspense since Cornell Woolrich.” Klavan is a contributing editor to City Journal, the magazine of the Manhattan Institute. His essays and op-eds on politics, religion, movies and literature have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the L.A. Times and elsewhere. Klavan is a frequent media guest on television and radio stations from coast to coast, where he is known for his quick wit, humor and commentary on politics and entertainment. He currently hosts the podcast The Andrew Klavan Show on the Daily Wire and his political satire videos have been viewed tens of millions of times. As a screenwriter, Andrew wrote the screenplay to 1990’s A Shock to the System, which starred Michael Caine, and to 2008’s One Missed Call, which stars Ed Burns and Shannyn Sossamon. He lives in Southern California. He has also written a memoir, The Great Good Thing: A Secular Jew Comes to Faith in Christ.

You’ve used other forms of storytelling, such as screenplay writing and journalism. What do you feel the novel writing form affords the storyteller as a storytelling medium?

The novel is my favorite form, hands down. Nowhere else can you create a world so completely and communicate with your audience so directly. In film, actors, directors and all the rest of the crew, add their talents to the mix—but they also stand between the writer and his audience. Conversely, the reader of a novel is mainlining another person's imagination, straight up. On top of that, since the points of view in the novel are expressed by characters with fully fleshed out personal lives and limitations, no voice needs to stand as "the voice" of the story. It allows for so much complexity, which is just more true to life than any other form I can think of.

What was it like working with Clint Eastwood on his 1999 film adaptation of your novel True Crime?

Well, I had very limited involvement. I met the guy. He was gracious, intelligent, and clearly had the mind of an artist. But when I sold the novel to film, I let it go and did not write the screenplay or get involved with the filming.

Were you involved in the film adaptation of your novel Don’t Say a Word (2001), starring Michael Douglass and Brittney Murphy, and if so, what was that like?

I wrote the first draft of the script—but the project spiraled into "development hell" and I ran for my life. It took ten years to make it to the screen, and by that time so many people had written drafts of the screenplay, I used to bump into them at parties, even overseas. I'd shake hands with someone and he would say, “Andrew Klavan! I wrote a draft of Don’t Say A Word,” and I would think, yeah, you and everybody else, my friend! Finally, there was a writer’s strike in Hollywood and Michael Douglas needed a project and he said, “Whatever happened to that movie we were going to do ten years ago?” So it got made. Then it opened right after 9/11. I remember when the towers fell, through the dust and chaos, I could see the bus cards for the movie. In the opening shot of the film, the Twin Towers appear (with my name over them!)—and the audience gasped aloud. The picture was a hit—I believe it was the first hit after the attack—but it was a sort of sad experience at the time.

“…stories work to transform us...”

With Another Kingdom, your latest novel based off of your smash hit podcast of the same name, you’ve begun writing deeply in the fantasy genre. What do you feel that the fantasy genre affords you as a storyteller?

Great question. Another Kingdom—if I say so myself—is a very cool piece of work, because it takes place in two worlds, but over the course of three novels, the two separate stories reveal themselves to be one big story. What this allowed me to do was to create a thoroughly modern world and plot and connect it at every point to a more fantastic, sword and sorcery world, which, for me, raised really complex and interesting questions about how those worlds are linked in our imaginations, how stories work to transform us and how moments poised at the very cutting edge of the modern are still bound by mystic chords to timeless and essential values and ideas. You can probably tell I’m very proud of the thing. I was immensely gratified by the success of the podcast (which was produced with the help of so many of my friends at the Daily Wire, I can’t name them all here), but I think people will really enjoy experiencing it direct off the page and as an audiobook. Again, that’s mainlining story in a unique way.

Are there any fantasy authors, or fantasy books, that influenced you in the writing of Another Kingdom?

There is no fantasy writing without Tolkien. He’s the ur text and if you don’t know him, you don’t know the genre. I was also very taken with the HBO show Game of Thrones, one of the best TV shows I’ve ever seen. Even before it came on, I’d been wrestling with the idea of doing a fantasy story that had a hard sense of reality. But when Game of Thrones came out and did that so well, I resolved to do something utterly different. I think the two worlds of Another Kingdom solved that problem. They also link the story to other so-called "portal stories," like the Narnia books. But while I’m a huge fan of C.S. Lewis’s non-fiction, his fantasy stuff is a bit too soft and pat for me. Still, I was aware of the connection and I do love his ideas.

“Fantasy worlds don’t mean anything if they don’t speak into reality in some essential way.”

In Another Kingdom, Austin Lively, a struggling screenwriter, is transported back and forth to medieval Galiana where he’s unwittingly charged with murder. Lively also confronts a powerful and murderous billionaire in L.A.—willing to kill for a treasure, while Galiana has just been taken over by the evil Lord Iron. Was it intentional that the fantasy world of Galiana mirror our own world, and if so, why?

Absolutely intentional. Fantasy worlds don’t mean anything if they don’t speak into reality in some essential way. There are no dragons, vampires, werewolves or zombies in real life, but all these things have meaning in the minds of humans. In coming up against unreal creatures, Austin, a wannabe storyteller, is forced to confront some of the most basic human ideas: the responsibilities of manhood, the mystic power of femininity, the need for different kinds of courage, and the potentially corrosive nature of temptation and desire. These themes have become all but unmentionable in our modern world. But I mention them plenty and use my two worlds to explore them, I hope, in a meaningful way that breaks through any politically correct nonsense.

“…let every voice be heard, let every imagination tell its tale.”

Having worked with Clint Eastwood, do you share his frustrations as a fellow conservative, working within the confines of a decidedly liberal media and publishing? Is the left at a loss for subscribing to mostly one-sided media and publishing?

It’s a tragedy of small-mindedness. I don't want to stop leftists from making films or writing books. I love some of their work. But conservatives are blacklisted in Hollywood and, to a lesser degree, in publishing, and that means all kinds of talented people are being silenced or consigned to hard-to-find venues. The trick the left uses is to deem anything they disagree with as hateful—racist, sexist, homophobic—all the garbage phrases they use. It’s a damnable lie and I condemn them for it. And you know what? Even in those rare cases where some sort of prejudice may actually exist (on left or right), I say: let every voice be heard, let every imagination tell its tale. I have great faith that good ideas will beat out bad ideas. Deep down, leftists know that too—that’s why they work so hard to silence us! Our ideas are better.

Do you have any advice for writers looking to become published authors?

You know what question writer-hopefuls ask me most? "What book can I read that would help me become a writer?" My answer is: not book. Books. All the books. You should know your genre cold, but you should also know the classics. You want to be a novelist and you’ve never read War and Peace, David Copperfield, Madame Bovary? You may be successful as hell, but you'll never be as good as you could be. And one other thing. I hate to say this, but nowadays it’s necessary. Get a high school grammar book and go through it from page one to the end, doing all the exercises along the way. There are still enough good editors who will turn you down for dangling a participle. And if they don’t, and you get published that way, you’ll look like a knucklehead. Plus, you’ll kind of be a knucklehead, which is even worse!

What can we look forward to in future books, following Another Kingdom?

Well, now that I’ve kind of fashioned this twist on the thriller genre—this suspense story that goes to the edge of reality and then goes over the edge—I’d like to develop it some more. But first, I have to finish the third novel in the AKtrilogy. And so to work.